I suspect the only thing J.D. Vance and I have in common are that we both grew up in working class families in steel mill towns in the midwest, and we both have grandparents who moved there from Eastern Kentucky after World War 2. That—along with the fact that I hadn’t brought another book to read on my flight home—was enough to convince me to buy his newly-published book Hillbilly Elegy at a magazine stand in the San Francisco Airport.

What I quickly realized after beginning the book was that he and I had a very different understanding of what led his family to leave Appalachia, why it is that so many people there are struggling to get by, and what the value of personal responsibility means in contrast to the issues Appalachians (and all working class people) face in this country.

It’s important to consider what Hillbilly Elegy means in the context of J.D. Vance now being Trump’s running mate (and unfortunately, very likely our next VP).

Let’s start by talking about the story Vance tells in this book and the picture he paints with that story of the people of Appalachia. It starts in his grandparents’ home in Middletown, Ohio where his mother grew up. His grandparents had moved there from Eastern Kentucky after World War 2 looking for better economic opportunity, which his grandfather found in a good-paying job at a steel mill. Even with financial security, his grandfather struggled with alcoholism and was abusive to his grandmother. After he was born, his mother struggled with drug and alcohol use and lost her source of income, which led to JD and his sister being raised mostly by their grandparents.

In this part of the story, he focuses all of the blame on the struggles the family face on the individual choices of those people. He does not give any thought or consideration to what external factors led them to those choices. Things like economic hardship, drug and alcohol abuse, and domestic violence are treated as individual failures, and in no real way connected to the systems of economic and social exploitation that are forced on working class people by the owning class.

The reality, of course is that in working class America, good grades and a positive attitude will only get you so far.

It is a mixture of pre-existing privilege and luck—or random chance, rather—that determines how financially and socially successful a person will be, and any number of circumstances outside of your control can influence that. Something a simple as a chronic health problem can strip away any chance of success by those metrics, even if you do everything right to counteract it.

There is also another critical aspect to understanding this success-versus-privilege problem, and that is the system in which we are forced to live. No matter what part of America you come from, there is a concerted effort on the part of the wealthy owner class to keep the working class people impoverished enough to depend on them, but just hopeful and proud enough to keep the wheels of capitalism turning (and… you know… not have us revolt against them). We can only succeed so far in a system that has no vested interest in a significant part of the populace being successful.

The second thesis of Hillbilly Elegy seems to be in Vance using his own story to concurrently paint a picture of his particular understanding of “hillbilly people.” Vance uses that term to describe himself as well as broadly all working class people from Appalachia, and all of the people—like mine and his grandparents—who left there on the “Hillbilly Highway” seeking prosperity (or at least stability) in the middle of the 20th century. While he seems to use the term endearingly, his use of it to ascribe a uniform identity and particular ways of thinking to what is actually a very socially and ideologically diverse people is incredibly reductive and pejorative.

To Vance, hillbillies as a people are their own worst enemy. They are ignorant to the world around them, lack the desire or drive for upward mobility, are given to addictions to drugs and alcohol, and are content to subsist on welfare and let the public school system raise their children for them. With absolutely no critical understanding of the circumstances that actually have forced many people in Appalachia into poverty, he again pins all of the blame squarely on the individuals, with no consideration to the systems that are forced on them.

The title “Hillbilly Elegy” alone is enough to understand what is wrong with Vance’s way of thinking.

It is the height of audacity on Vance’s part to insinuate that the story of Appalachian working class people is a tragic tale of a failed culture, an elegy for the death of Hillbillies’ potential to succeed and thrive. No one person has the right to speak definitively for (or of) a diverse group of people like Appalachians. Vance especially does not have this right, as he is only tangentially connected to the region and people he claims to understand. By his standards, I have as much of a right to speak about Appalachia as he does.

I can’t argue that Vance’s troubled upbringing did not afford him the advantages that many of his privileged political colleagues had, but the reality is that his career has come to the point that is not just because he found “stability” or because he worked harder than others, but because wealthy benefactors like Peter Thiel have put their thumb on the scales of his life. I can and will argue that an investment-banker-turned-career-politician who has never consistently lived in Appalachia has no right to be the spokesperson for working class people there or anywhere.

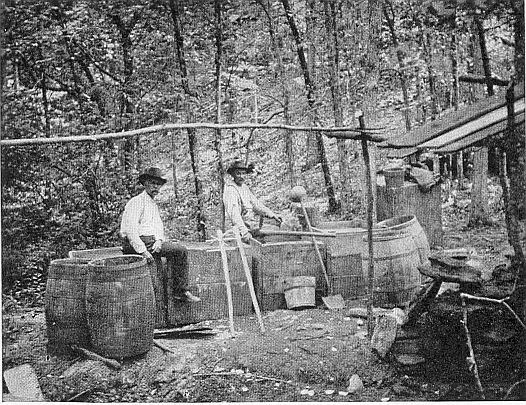

The truth of Appalachia is much more complicated than Vance even begins to describe it to be. It is not a homogeneous culture of poor, white, Christians. It is one of the most ethnically, culturally, and socially diverse places in this country. It is a place where Irish settlers like my ancestors found a home escaping the Drochshaol, where the militant labor movement fought battles like Blair Mountain to give workers rights in the face of forced poverty, and where people of all ethnicities interacted with solidarity decades ahead of the rest of the country.

Appalachia’s enemies are not Appalachians themselves, but those who have continually historically exploited them: the coal barons who made wage slaves of its people, the federal government that drowned it’s hollers with dammed up rivers and destroyed it’s fertile soil with kudzu, and the white supremacist carpet baggers who whitewashed away its rich ethnic diversity. More recently it’s the retail chains that drive all of it’s communities’ small businesses into bankruptcy and the pharmaceutical corporations that flooded the region with opioids.

The struggles Appalachia face are also not all unique to that region. In Middletown, Ohio where Vance’s grandparents settled or Muncie, Indiana where mine did, or anywhere where working class people live, the reality is the same: the owning class exploited the working class, giving them just enough of a taste of success to keep them in line, and then leaving them and their descendants to struggle against a broken, uncaring system, stoking racial and social violence to keep them from attaining any kind of class unity.

Vance’s political ideology is the ultimate expression of his broken view of the working class struggle in Hillbilly Elegy.

When I first read the book, it seemed like just another uncannily bad neoliberal take on working class life, but understanding it now as the kind of half-memoir-half-manifesto of a high-ambition career politician, its thesis is clearer and more terrifying. In Vance’s worldview, rugged individualism is ultimately the key to success. Anyone who is incapable of their own volition of escaping the systems of poverty, racism, and violence that they are born into does not deserve success. More than that, they alone are entirely to blame for their failure if they are unsuccessful.

Systems which seek to lift people out of poverty by providing for their material needs like food, housing, and healthcare are—in Vance’s worldview—making people weak and lazy. His view of public education is that it is not a system made to ensure that all people have the basic knowledge and skills to be a conscientious member of society, but a place where children are dumped off by their parents to be raised by the state and taught a radical political agenda.

At the heart of Vance’s beliefs is a subscription to the ideals of neoreactionary thinking, a.k.a the “Dark Enlightenment,” popularized and firmly idealized by his friend Curtis Yarvin and wealthy benefactor Peter Thiel. This is a dangerous philosophy that rejects the notion of humanity’s political progression towards more social liberality and democracy being beneficial. In the eyes of neoreactionaries, the ultimate form of government is totalitarianism under a sort of hybrid of monarch and corporatocracy.

With Hillbilly Elegy, J.D. Vance makes it clear that he believes himself to be qualified to speak definitively for millions of people from which he does not come, whom he holds in contempt for their supposed laziness and ignorance, and from where he builds a worldview that leaves no room for nuance. His political ideals in response to this seem to be that civil rights, human liberties, and even democracy itself are entirely regressive. And now, he is very likely to be the United States’ next Vice President.

Be First to Comment